True Forensics Uncovered SE01 E02: The Opportunist

Motive, means, opportunity (MMO). In criminology, these are the 3 factors investigators establish to solve crimes. Motive is the assailant’s reasons for committing the crime. Means are the tools or methods they use.

Opportunity is the circumstance that allows the crime to be committed. The same framework applies in cyber security. Motive and means are both crucial considerations for organizations building a defense against identifiable threats. Yet, opportunity can be the greatest determining factor leading to an attack.

This is a story about exactly that. It wasn’t anything personal. And the attacker hadn't spent months researching and crafting their approach; the victim was targeted for no reason other than the attacker could. How they would follow through from a successful compromise to criminal gain could come later.

Cyber forensics after eradication

Once you know a domain has been compromised, you must also assume that a vulnerability now exists in your defenses. If it’s been exploited once, it can be exploited again. Therefore, it must be identified and fixed quickly to stop the same attacker or others using it to get in. In these situations, our incident response (IR) team is brought in after containment and eradication. Together with the client, we’ll piece together evidence to unravel how the attacker gained their foothold and develop the means to stop any recurrence.

One case just like this came my way when the team was called by a national CERT. We were asked to help a global communications & connectivity provider that had itself suffered domain compromise. Even with the help of its existing security vendors, it couldn’t find the attacker’s entry point in their perimeter. The attacker had managed to authenticate to the VPN and attempted to harvest credentials for the entire domain by taking a copy of the ntds.dit database. Thankfully, the organization detected them on the network, stopped them, and was able trace their activity back to a VPN gateway. And yet, all the VPN gateways were patched and there were no known/identified vulnerabilities on the perimeter. How had the attacker acquired the necessary credentials to launch their attack?

Building a profile

In forensics, accuracy is king. Every piece of evidence must be scrutinized before it can be used to uncover the full attack chain. For me and the rest of the IR team, that means validating the “facts” provided at the outset of our investigation. In this case, we requested access to:

- The findings from the EDR and network monitoring providers

- VPN gateway application and system logs

- Images of the impacted hosts

Confident that the evidence we needed to pinpoint the attacker’s route in was hidden somewhere in this data, we began to unpick the incident…

The vendor reports

Reading through the EDR and network monitoring reports, I couldn’t help but notice that the attacker’s execution pattern matched open source Impacket tooling. I’d seen it many times before when confronting other threat groups. The report from the network monitoring provider also highlighted the detection of certain strings in network traffic, including:

- ExecMethod

- Bind

- SetClientInfo

- NTLMLogin

- GetObject

- EstablishPosition

- RemRelease

- GetSmartEnum

- GetResultObject

- GetCallStatus

- CreateInstanceEnum

- ComplexPing

- ExecQuery

All of these strings are functions explicitly present in secretsdump.py, an Impacket tool designed to perform credential dumping while leaving nearly no evidence on disk. Already, we’d uncovered one piece of the puzzle—the attacker’s means.

The VPN application logs

We turned next to the VPN application logs to perform a rotating pivot analysis (RPA). Log “pivoting” is the process of matching log entries with indicators of malicious activity. Our own RPA technique pivots continuously from one or more malicious IP addresses to compromised accounts, and vice versa, until no further indicators of compromise remain. At this point, you can be confident all evidence available has been collected. Step-by-step, the process looks like this:

- Search log entries attached to a malicious IP address to reveal all associated entries

- Identify the user accounts accessed with the malicious IP address to identify which and how many were compromised

- Search all log entries attached to those compromised users to identify every IP address that used their accounts

- Remove IP addresses related to the organization

- Repeat process for new IPs until no new malicious IPs can be identified

In this particular case, our analysis uncovered multiple IP addresses and compromised accounts missed by the vendors. We had our first breakthrough. November 10 was not—as the reports had established—the date that malicious activity first began. It was October 30 instead, 11 days prior. Suddenly, a new window of time opened for us to investigate.

Validating the facts

As I mentioned, one of the key facts provided at the outset of our investigation was that all VPN gateways were patched. But when we observed activity from a few days prior to the attack, a different reality emerged. One of the VPN gateways had in fact been running a critically vulnerable version (CVE-2019-11510) for almost 1 week prior to October 30. It was rebooted back to the current version during a period of maintenance with none of the security team any wiser. Why the initial regression? Well, this was down to the VPN’s legitimate functionality and nothing more; if one such system fails to boot, or experiences any other critical failure, it will roll back to a previously installed version. Buried deep in the system logs, this signifier of the attacker’s origins had been missed through simple human error.

We also found that an open source intelligence (OSINT) alert had detected mass scanning and exploitation of VPN gateways for CVE-2019-11510 around the same period. Joining the dots, we started to visualize how the attacker got through the client’s perimeter:

- Around the end of October, one of the VPN gateways rolled back to an older version with vulnerability CVE-2019-11510.

- Mass scanning and exploitation took place across the internet around that time for said vulnerability.

- An attacker identified our client as a potential target.

- Via a simple web request, the vulnerability enabled the attacker to perform an arbitrary file read and intercept active credentials for the VPN gateway.

- The attacker logged on to the VPN gateway and exported its configuration (config) files.

Timeline analysis: an unexpected discovery

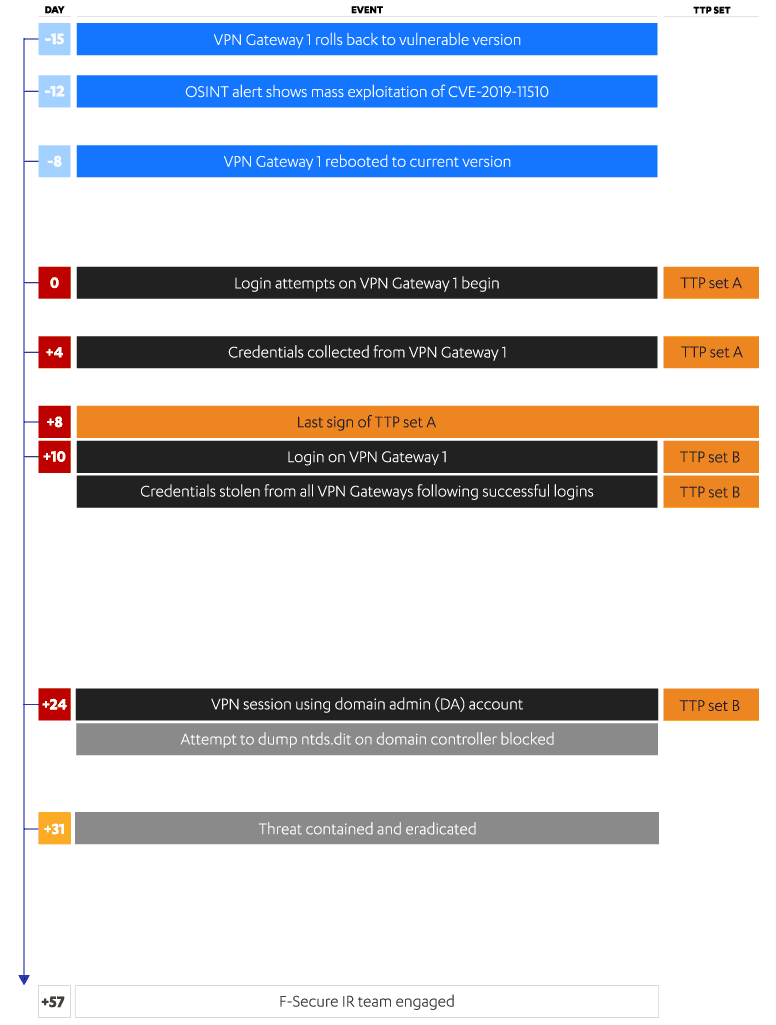

We organized all the VPN gateway and system logs into a timeline to help us understand how the attacker had traversed from their initial foothold. Strangely, we found ourselves looking at not one, but two sets of TTPs.

Fig. 1. Timeline of attack taken from system and VPN logs and the incident timeline.

We’d all assumed—until now—that we were dealing with one attacker. One attacker with two sets of TTPs though? That didn’t make sense. So, I returned to the timeline and examined it again with fresh eyes. It didn’t take long to hit me that the attacker’s working hours didn’t add up. Until day +8, activity could be attributed to Eastern European Time (EET). From day +10 they drastically changed. We were seeing not one, but two attackers...one in Eastern Europe and one in Asia.

The European attacker managed to gain their foothold and perform some malicious activity, but ultimately struggled to advance their attack beyond this stage of the kill chain. Then on day +10, the attacker in Asia shifted up a gear from the earlier activities. They were clearly a more capable and motivated threat, ultimately leading to the compromise of the domain and significant data exfiltration. The fact they exported the config files for all the client’s VPNs told us that they had also performed detailed research on their victim—they knew what was on offer. Their use of Impacket tooling made sense too. Popular with many of the Asian APTs I’d seen in the past, the tool’s ability to clean up after itself, leaving no trace except logs for file creation and deletion, is particularly attractive to APT groups.

Diagnosis and recommendations

Our investigation had unveiled not one but two attackers utilizing the same vulnerability patched by the client long ago. We will likely never know what the relationship was between them. It could have been groups working together. More likely, the first quickly recognized their limitations and monetized their access by selling the extracted credentials to the second, more capable threat actor.

The client had taken measures to uphold their security posture by applying a patch to their VPNs, then by engaging multiple security vendors when things went wrong. It was the functionality of their VPN gateways—prioritizing availability over security—that gave two opportunistic attackers a way in, with little indication of how.

It can take less than 24 hours for a threat actor to deploy a continuous, automated cycle of exploitation in the hope of gaining access to as many networks as possible. You need only look at the saga from Microsoft Exchange to appreciate the perpetual race between attackers exploiting and defenders patching. As a result, our recommendations focused mostly around further domain hardening on the estate (which overall was in a very reasonable condition). We encouraged them to adopt a continuous approach to their external asset mapping activities and proactive vulnerability management. Both can help minimize the window of opportunity that attackers have to exploit new vulnerabilities in future.

Reflections

An attack without a clear motive is hard to discern at first. It was because of our collective experience as a team that we could effectively scrutinize existing evidence, find more, then connect the dots. Not only did we identify two attackers, but our first-hand knowledge of APTs enabled us to develop threat intelligence (TI) around the more dangerous of the pair. This would ultimately go on to help the client expand its security strategy to address the means and motive of this adversary.

A threat-centric approach, where risk is informed by known threats with motives and means, is necessary for organizations to effectively increase your security posture with the right investments. But you are at risk also if you overlook the attackers that will exploit incidental situations that are unknown-unknowns until (of course) they happen. These opportunists can in fact pose a greater risk. They might have no prior intention to target you, nor have even heard of you, until the opportunity arises. The key learning is to minimize the opportunities you present to them. Denying easy access and raising their costs will prove an effective deterrent to all but the most capable and committed adversary.

Related resources

True Forensics Uncovered SE01 E04: Judgment Day

Some investigations are the tip of the iceberg. With deeper forensic investigation, it’s possible to get below the surface and reveal a much greater, persistent risk putting an organization in danger.

Read moreTrue Forensics Uncovered SE01 E03: Too Close to Home

Lifting the lid on cyber forensics with a true crime thriller. This first article in a new series shows how investigators uncover evidence during an incident and use it to contain and eradicate the attacker.

Read moreTrue Forensics Uncovered SE01 E01: Hidden in Plain Sight

Lifting the lid on cyber forensics with a true crime thriller. This first article in a new series shows how investigators uncover evidence during an incident and use it to contain and eradicate the attacker.

Read moreIncident readiness & response

WithSecure's™ cyber security experts pre-empt, prepare for & counteract cyber security incidents with state-of-the-art incident response software and solutions.

Read more